From December 13 to 18, the World Trade Organization will hold its sixth ministerial meeting in Hong Kong, China, to negotiate the fate of public services, the global food supply, and jobs and development. Representatives from 148 countries will meet to shape the future of the global economy.

Negotiations are stalled on a variety of issues, and it’s possible the Ministerial may end without a consensus Declaration. WTO proponents are attempting to portray the crisis in negotiations as though the problem were the lack of European (particularly French) or Brazilian « ambition » to break through the deadlock.

But the real issue is that the WTO is in crisis because the model of corporate globalization has failed to produce economic growth, its supposed mandate. For 10 years, the WTO has helped to promote a surge in global trade — and yet this increase in trade has failed to raise economic growth, even to the levels achieved during the pre-1980 era. It has also failed to alleviate poverty. According to the United Nations, we still live in a world where 24,000 people die worldwide every day from hunger and poverty-related diseases.

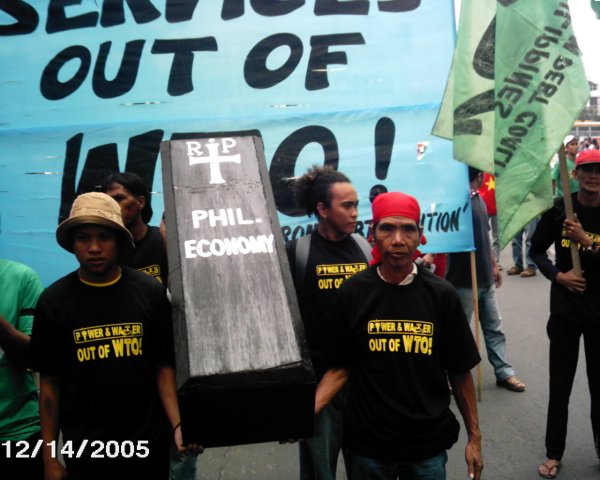

Now that the record is clear, global social movements and many governments are questioning the WTO’s attack on sovereignty, democracy and the ability of poor countries to develop. Thousands of farmers, workers, environmentalists, women, people of faith, immigrants, and human rights advocates from Hong Kong, Bolivia, South Korea, Canada, South Africa, Indonesia, Europe, the Philippines, the US, and other countries, will meet in Hong Kong this December, to protest the undemocratic WTO and its destructive impact on communities, democracy, development, and the environment.

A broken model

The WTO aims to consolidate a series of policy reforms that many countries have implemented over the last 25 years, following IMF and World Bank structural adjustment programs in developing countries, and Reagan-Thatcher prescriptions in the US and Europe. Referred to as « free trade, » « the Washington Consensus » or what we call « corporate globalization, » the policies include privatizing public services, weakening labor laws, deregulating industry, opening up to foreign investment, shrinking the non-military government, lowering of tariffs and subsidies, and focusing on exports over production for national markets.

This time period has seen a sharp decline in economic growth worldwide.

The WTO has failed to produce economic growth because this entire model is actually geared to increase the power of corporations in the governance of the global economy. Rather than governing just trade, the WTO is better understood as a global corporate power-grab, aiming to impose a one-size-fits-all set of rules on national issues of public services, intellectual property, agriculture, industrial development, and more. Under this flawed model of corporate globalization, not only is economic growth sluggish, but economic inequality has vastly increased, diminishing prospects for development and the attainment of universal economic human rights.

Best case scenario: less than a penny a day

Not only is the WTO’s record dismal, but future prospects look even dimmer. Even according to traditional economic models, new figures show much less global economic growth from the current WTO round than originally projected. In the recent study released by the World Bank, a successful outcome in the current negotiations could expect global economic gains of a mere $3 to $20 a year per person worldwide by 2015, of which more than two-thirds would go to the rich countries.

But one of the most fascinating conclusions of the study was that gains from complete trade liberalization worldwide — a highly unlikely scenario — would amount to a mere $287 billion in 2015. Seems like a big number, but that’s a paltry 0.7 percent of global GDP projected that year.

Let’s put this statistic into reality. Imagine living in a country where your annual income is a buck a day. Under complete trade liberalization, according to one of its greatest proponents, your dollar a day income would rise to a buck and 7/10ths of one penny.

That’s why over 130 groups — led by trade unions — around the world have released a statement called « The Doha Development Round: a recipe for the massive destruction of livelihoods, mass unemployment and the degradation of work. » The statement begins, « When the world’s trade ministers put their signatures to the founding document of the WTO in April 1994 in Marrakech, their very first sentence establishing the WTO committed them to raising standards of living, ensuring full employment and a large and steadily growing volume of real income.

« Has the Marrakech miracle materialized? Are employment and livelihoods ensured and steadily growing? No. The WTO’s trade and investment rules have taken the world in the opposite direction, and the current negotiations threaten to take us further still. After ten years under the WTO, unemployment has climbed around the world. »

Other economic models have historically delivered much higher levels of development than the supporters of the WTO model claim to offer, such as those used by many developing countries before the IMF started controlling their economies. In addition, other models — such as focusing on investments in health care and education — have proven to alleviate poverty far more effectively than just focusing on trade and investment liberalization.

For example, the two fastest growing economies in Latin America — posting growth around nine percent this year — are Argentina and Venezuela, which have both followed unorthodox economic polices that are not favored by international financial institutions and the leaders of the WTO.

The International Forum on Globalization’s seminal collection, « Alternatives to Economic Globalization: A Better World is Possible, » highlights a number of these policy alternatives, culled from some of the most luminary thinkers on these issues from around the world, including Walden Bello, Vandana Shiva, Jerry Mander, Lori Wallach, and others.

Up for grabs: services, jobs and agriculture

On December 1, the Director General of the WTO, Pascal Lamy, distributed a second draft of the proposed Declaration that the WTO Ministerial meeting will discuss in Hong Kong. Many developing countries reacted swiftly in Geneva, voicing serious concerns about the text, as it overly represents the interests of developed countries and corporate interests at the expense of development issues.

So what’s really happening in the WTO?

Services:

In recent years, corporations have fought to redefine « trade » to include services. Rather than seeing that services like water distribution, health care, and education are human rights, the WTO aims to privatize these public services, which would increase corporate profits but limit access for the poor. That’s why social movements in Bolivia and other countries are launching a new campaign, « Water Out of the WTO. »

Rich country negotiators also want to deregulate private sector services, like electricity distribution, banking, and tourism, by restricting public oversight over corporations. Just what we need: less regulation of key industries like accounting and energy distribution, so we can have more Enron and Arthur Anderson scandals.

Unsatisfied with the number of services developing countries have offered to be sold off to foreign multinational corporations, the US and Europe have made recent demands that countries offer a minimum number of services for complete liberalization. This new demand has met with stiff resistance from developing countries, who see through the maneuver as a corporate grab that would prevent their achievement of Millennium Development Goals like increasing access to health care and education.

Even more controversial are the talks on increasing visas for foreign workers, or « the movement of natural persons » in WTO-speak. The WTO should not be setting domestic immigration policy, particularly as the proposed rules drastically limit immigrant workers’ labor rights, and would contribute to the global brain drain in developing countries.

Jobs and Natural Resources:

In another key area of negotiation, rich countries are pressuring poor country governments to lower tariffs on industrial products and natural resources (Non-Agricultural Market Access, or NAMA). Using tariffs to protect new and developing industries against competition from foreign products is a cornerstone of industrial policy, one that every developed country has used to protect jobs and national industries. If negotiations continue, the WTO would kick away the ladder of development — permanently.

In addition, NAMA would increase trade in important natural resources such as forest products, gems and minerals, and fish products, and tear away at « non-tariff barriers » that we call health and safety regulations.

Tariffs are essentially taxes on corporations for the privilege of making money in a foreign country, so tariff reduction should be understood as a giant corporate tax abolition scheme. If corporate interests get their way, rich countries will be able to force developing nations to drastically reduce their tariffs. Then many small developing countries, which depend on tariff income as a significant chunk of their national budgets, would see financing for health care and education siphoned off radically.

The Third World Network’s Martin Khor has called the NAMA negotiations the « end of development. »

Agriculture:

Land reform, food subsidies for the poor, and sustainable production are core elements of a fair and healthy food system. But the WTO rules are based on an ideology of food for export, not for eating.

The main points of contention in the agricultural negotiations are government subsidies for domestic production, and tariffs on imports. But the US and Europe, with stunning hypocrisy, have largely won exemptions for the types of subsidies they use, which largely benefit agro-industrial corporations like Monsanto and Archer Daniels Midland. The global farmers movement Via Campesina has launched a « WTO Out of Agriculture » campaign because small farmers worldwide have witnesses their livelihoods destroyed for the last 10 years due to WTO policies.

Readers might remember the tragic suicide of Korean farmer Lee Kyung Hae during the Cancún WTO ministerial two years ago, wearing a sign that read « WTO Kills Farmers. »

This time, the Ministerial is presaged by such a tragedy. During Bush’s visit last month to a Summit of Asian and Pacific Economic Cooperation, a young Korean farmer killed herself by drinking insecticide — to protest the deadly WTO farm policies of allowing massive importation of foreign subsidized rice.

Window of opportunity

The potential failure of the sixth Ministerial will actually throw the WTO into a deep crisis. After failing to launch the so-called Millennium Round in 1999 in Seattle, this current round of negotiations was launched in Doha, Qatar in 2001. A second ministerial collapsed amidst massive civil society protests in September 2003. Negotiations were supposed to have been wrapped up by January 2005, yet are still stalled on the basic framework.

If the framework (modalities, in WTO-speak) is not completed by March, it will be extremely difficult for negotiators to wrap up the technical negotiations in time to send the final agreements to the US Congress before the expiration of Fast Track negotiating authority in July 2007.

The sixth Ministerial of the WTO follows on the heels of another failed Ministerial, the Summit of the Americas in Mar del Plata, Argentina. The Bush administration attempted to use the meeting to jump-start the stalled FTAA talks, but the meeting ended without even a declaration. This failure was widely interpreted in the mainstream media as an indictment of the entire model of corporate globalization in Latin America.

If developing country governments, in conjunction with global civil society, can stand up to the pressure of US and European arm-twisting and outrageous demands, the Hong Kong Ministerial could fall apart again, just like Seattle, Cancún, and Mar del Plata.

In the US media, we will likely hear about the lack of European or Brazilian « ambition » to break through the negotiations deadlock. But the truth is clear: The radical experiment of instituting a global corporate government has failed to deliver economic growth, development, or democracy, and never will.

It’s not just the negotiations that are broken, it’s the model.

The next few months offer a crucial window for us to turn back the tide of corporate globalization — and instead build a vision of a global economy based on life values, not money values. Let’s not miss the opportunity.

Deborah James is the Global Economy Director of Global Exchange, and will be present at the WTO Ministerial in Hong Kong.

Deborah James, Global Economy Director